Initially, when watching Tár you may be tempted to compare it to a fictional biopic. After all, it follows the story of a highly successful woman in music, highlights her passion, and is dramatic! It may even remind you a bit of Whiplash or Black Swan, as these movies also follow an obsessed artist with a crumbling psyche. (If you’re interested in this type of genre I would highly suggest watching: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ba-CB6wVuvQ).

But I think Tár is different.

While Black Swan’s protagonist believes her suffering was ‘worth it’ because she ‘was perfect’ and Whiplash’s protagonist finally gains approval and a chance to showcase his hard work, Tár’s main character Lydia just keeps devolving into an abusive figure.

When we’re introduced to Lydia she’s already at the top of her career and seems to have it all. She has awards, a dream job, a family, and is climbing up the music world’s political chain. But throughout the film, her actions become her downfall.

So, I want to discuss my thoughts on this film because it still gnaws at my brain since I watched it in the cinemas all the way back in early February of 2023 (yes, Australia still gets some films super late).

Firstly, we should read this extract from What “Tár” Knows About the Artist as Abuser by Tavi Gevinson (published November 24, 2022):

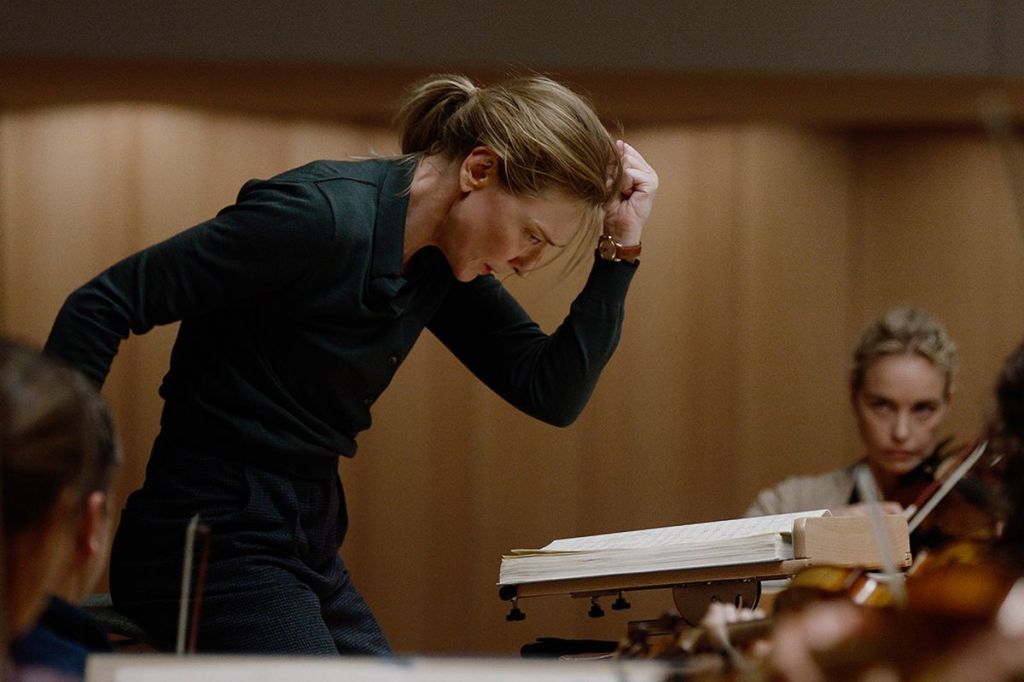

Of all the disturbing scenes in “Tár,” Todd Field’s movie about the downfall of a world-famous conductor, I was most haunted by a frame of the titular character laughing. Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett) is driving a young cellist named Olga home from a private rehearsal in Lydia’s apartment. By this point in the film, we have spent nearly two hours closely observing the artistic rigor, tasteful luxury, and careful self-promotion that characterize Lydia’s daily life. Her movements are agile and precise. Her words hang in the air, sonorous with authority. She appears to possess the inner peace of someone with a steady spiritual practice, and invokes Jewish mysticism to discuss her work as an interpreter of music. She is also egomaniacal and inaccessible, and she evades accountability in even the most trivial interactions. At home with her partner and her grade-school-aged daughter, who addresses her as Lydia, she often seems to be somewhere else. The audience, too, is held at arm’s length; we know more about Lydia’s professional credits than about her origin story. She does not fit the mold of an openly tyrannical boss or an irate, bullish tycoon. She is, more chillingly, able to control her surroundings through the artful subtlety of a cold stare, a warm hand, or the rebuffing of a too-needy request. By the time she drives Olga home, Lydia’s worse transgressions are catching up with her. She seems to have a habit of taking her young female acolytes as lovers, and now a jilted former mentee, Krista, has died by suicide. But Olga, sitting shotgun in Lydia’s car, is rosy-cheeked, disarmingly unmannered, holding a stuffed animal. She playfully pushes the toy in Lydia’s face and laughs. Lydia, caught off guard, laughs back.

Watching her mask momentarily fall, I felt a flash of recognition. This was the expression of temporary abandon I’d seen on the faces of male artists enlivened by relationships with younger women. It was not simply the face of a predator seeking renewal from young flesh but the face of an older artist suffering a creative impasse and therefore an identity crisis. Through the attentions of an unjaded young woman, the artist momentarily recoups a lost memory of unbridled joy. You can see a version of this face on Woody Allen’s comedy-writer character in “Manhattan,” beside himself at the childlike wisdom of Tracy, the seventeen-year-old he makes his girlfriend. You can imagine it, reading Joyce Maynard’s memoir “At Home in the World,” when a fiftysomething J. D. Salinger tells the prodigal author, then nineteen years old, “You know too much for your age. Either that, or I just know too little for mine.” Both of those works feature men telling young women how corrupted they will be by the outside world, and by their creative fields in particular. The men don’t acknowledge that they, too, are corrupting forces. Perhaps, however unconsciously, they even relish the chance to be the first. I recognize the face from my own life, from situations in which I felt chosen, thanks in part to works like “Manhattan,” which make the exchange between a teen girl’s youthful energy and an older man’s knowledge seem as symbiotic as any relationship found in nature.

The face on Lydia is tragic, because it suggests that, at the apex of her career, she can surrender to unselfconscious expression only through interactions tinged with predation. Conducting has become inextricable from her sexually charged relationships with members of her orchestra, and from the godlike power she feels at the podium. Describing the feeling in a staged interview with The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik (playing himself), Lydia says, of her role as a conductor, “You cannot start without me. I start the clock.” Through conducting, she can stop time, reset it, accelerate it. She can also ignore phone calls, delete incriminating e-mails, lie to her family, obstruct careers, manipulate institutions, change her name, and create, as artists do, something that didn’t really exist before: Lydia Tár. She’s crafted herself in the image of great men, and insists that her gender hasn’t inhibited her career in any way. When intimidating her child’s bully in the schoolyard, she introduces herself as “Petra’s father.” By creating a character who can’t be written off as another predictably problematic man, “Tár” draws our attention to how Lydia learned to become one. And, by following Lydia closely, the film relieves the audience of a neurotic cultural obsession with the artistic legacies of real-life powerful figures, focussing instead on their tools. In lieu of asking “Can you separate the art from the artist?” or “But what will happen to these poor, bad men?,” “Tár” asks, “What does power look like, feel like, not only within an institution but within an individual psyche?”

I think this is a wonderful interpretation of the film, however, I think there is another lens from which we can view Lydia’s character. While I agree with the first paragraph regarding Lydia’s actions, from the second paragraph onwards Gevinson interprets Lydia as a rather tragic character.

My own interpretation is less heroic and less grand though. I believe that the film can instead be easily explained, and lacks greater meaning. This is because Lydia’s actions can easily be chalked up to her just being on the anti-social personality disorder (ASPD) spectrum.

ASPD is a mental health disorder characterised by disregard for other people. Those with antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) may begin to show symptoms in childhood, but the condition can’t be diagnosed until adolescence or adulthood.

Those with ASPD sorder tend to lie, break laws, act impulsively, lack regard for their safety or the safety of others, lack a sense of guilt, show no remorse for their behaviour, antagonise others, and manipulate or treat others harshly or with blunt indifference.

It is important to note that ASPD is a spectrum. For example, there are psychology studies suggest that people with ASPD who are caught violating crimes usually have lower IQs and come from abusive backgrounds. They also usually lack self-awareness and genuinely believe they are better than others. People with ASPD who are in high-level corporate roles usually come from an educated/privileged background though. They are more aware of how to manipulate others and have a single-minded determination that they use to their advantage to better their career. Then, people with ASPD who have a higher IQ and high level of self-awareness may tend to have depression and suicidal tendencies, and they can’t ‘fix’ what is ‘wrong’ with themselves.

But enough about ASPD. I shouldn’t dive too deep into the topic because it’s very under-understood and misunderstood by the general public due to fictional media, and academics don’t have many volunteers with ASPD jumping at the chance to be involved in research (either because they don’t realise they may have ASPD, or they realise they do and therefore don’t want to participate due to stigma).

One of the perhaps more accurate representations of ASPD in a person who is considered ‘well functioning’ in society is Brad Pitt’s character in Ad Astra. This character from the beginning of the film narrates how he feels a lack of adrenaline in adrenaline-inducing activities, always reacts logically, and doesn’t panic.

Lydia showcases many traits of someone with ASPD. She likes to be authoritative and in control of all types of situations. She frequently cheats on her wife, is very concerned with appearance, lies easily, manipulates well, and only becomes distraught when her child is taken away from her when she cannot control the situation. People with ASPD can also tend to hyperfocus, such as how Lydia’s main goal is to prepare for the concert and nothing else matters in her life and can be ignored until the concert is finished.

Lydia also, in my opinion, shows no sign of an identity crisis. She’s always in charge and likes to be controlling the situation. She purposefully doesn’t tell her wife that she’s stealing her pills, she lets her wife ignore her affairs, and she doesn’t seem enlivened by young artists. Instead, she’s interested when she wants to pursue them sexually. She doesn’t struggle with the ethics of her actions, and is only upset by the consequences when things don’t turn out her way.

While this idea is probably much less interesting than Gevinson’s, I don’t think that Tár requires such deep thought if you don’t want it to. Perhaps it can just be viewed as the story of a woman whose actions have consequences.

What do you think?